KVR History

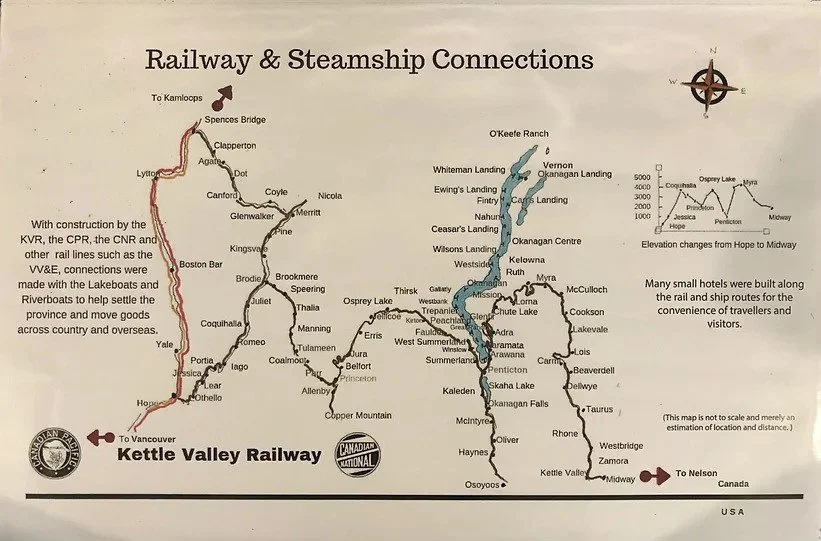

The Kettle Valley Railway route from Midway B.C. to Hope B.C. a total of 477.5 km.

(296.7 miles)

The Kettle Valley Railway (KVR) was built by the CPR to connect its mainline with its trackage in the Kootenays by a direct route along the southern border of British Columbia. The mainline of the KVR ran from Midway through Penticton, Princeton, Brookmere and then over the Coquihalla Pass to Hope BC, a total of 479 km ( 297.6 miles). The route over the Coquihalla Pass was the most difficult section of the Kettle Valley Railway and the section which accounted for much of the railway's reputation as an engineering marvel. The lowest summit over the Pass was 1111 metres (3646 feet). At the start of the twentieth century there were few people who could envision the engineering required to build a railway that could be carved out of some of the most rugged and inaccessible sections of the mountains.

The KVR as we know it began construction just after the turn of the 20th century (1910). The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) were anxious to secure rights to the rail access in the Kootenay region, as the Americans were connecting north from Spokane and Republic and a line to the BC coast would mean that the CPR had no access to the trade routes. The president of the CPR Thomas Shaughnessy, was determined to build a rail line from the coast to the Kootenays to protect his investment in trade in British Columbia. James Warren, who was the representative for the fledgling Kettle River Valley Railway was delighted to become president of the Kettle Valley Railway with a commitment to build from Midway to Merritt and across the Hope Mountains to Hope. Mr. Shaughnessy also chose Andrew McCulloch as the chief engineer for this new project. McCulloch had already been involved with the building of nearly all the CPR lines in southern BC and many other parts of Canada and the United States.

It has become known as one of the more remarkable rail lines ever built in North America. At the time there was a need to connect the interior of British Columbia with the coast, to enable better transport of goods and secure the area lying along the Canada/US border. An engineer named Andrew McCulloch was assigned the job of designing and building the route through these dangerous mountain passes. He was more than up for the challenge and it wasn't long before the KVR was nick named McCulloch's Wonder because of the amazing feats of engineering that were designed and built with Andrew McCulloch at the helm.

McCulloch working closely with James Warren, using surveys and the directives provided by Shaughnessy, decided on a route from Midway along the west fork of the Kettle River and across the 4300 foot Hydraulic summit, later named McCulloch in honour of the KVR's mastermind. The route would then descend into Pentiction along the mountainside on the east side of Okanagan Lake. Heading north from Penticton through Trout Creek Canyon and up to Osprey Lake. From there it went overland to Otter Summit, which we now know as Brookmere. At this point the rail line would split, with one going down to the Coldwater River valley where it joined the existing route at Merritt and the other heading southwest through Coquihalla Pass to Hope. This last was considered a branch line, but was in reality the mainline of the KVR.

Andrew McCulloch was faced with many challenges in building the KVR - the difficulties of getting workers, the engineering obstacles they faced both in construction and travelling through the region to oversee the work and ultimately the onset of WWI which created no end of shortages in supplies, funds and workers. Amazingly, by July 1916 the final section of the route connecting to Hope through the Coquihalla Pass was opened and the KVR was complete. The dream of a Kootenay to the coast rail line was now a reality.

The route over the Coquihalla was abandoned in 1961 in favour of the longer but easier line via Merritt to Spences Bridge, where it joined the mainline.